This event marked another edition of discussions bringing together Christian teachers, educators, pedagogues, psychologists, students, and parents. The Congress was hosted at the Jagiellonian Academy, with the Nicolaus Copernicus Academy serving as the main partner.

The program combined workshops and a series of lectures devoted to technological addictions, understood metaphorically as a “digital leash.” Participants engaged with reflections grounded in empirical research and in the professional experience of specialists in psychology, pedagogy, education, and cultural animation.

Across six workshops and eight lectures, speakers addressed topics such as adolescent brain development in the age of screens, the impact of algorithms on attention and emotions, challenges of upbringing and identity formation in the online world, and early childhood and preschool education in the face of digital change. These sessions created space for shared reflection and the exchange of practical experience.

Throughout the Congress, speakers presented guidelines and examples—rooted in Christian ethics—for building education based on relationships, values, and human dignity. The workshops proved highly inspiring. Participants left with concrete tools they can apply in their work with children and adolescents and share with other professionals and parents in their own communities.

Does Technology Change Students’ Relationships with the World?

Breaking the digital leash begins with understanding whether digital technology supports freedom of thought, critical thinking, and access to reliable sources—or whether it instead leads to dependence.

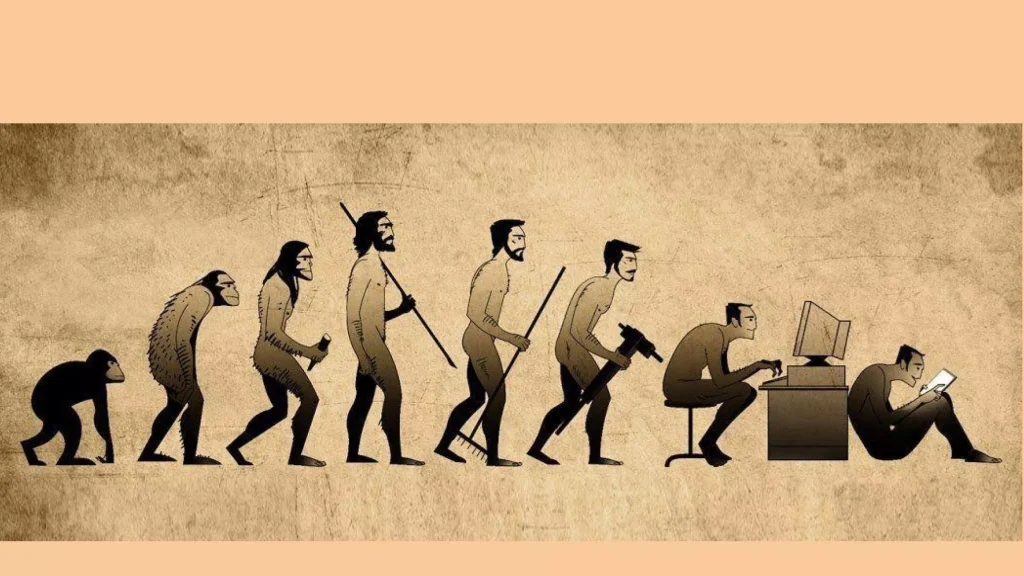

Father Dr. Andrzej Jankowski, a lecturer at the Jagiellonian Academy in Toruń, explained how digital devices train the brain for electronic multitasking and a fast-paced rhythm of life. This pace leaves little room for deeper reflection and gradually makes the slower, offline world feel unattractive.

Drawing on statistical data from research by Hodolska and Buks (Kraków, 2025), he illustrated the scale of phonoholism—smartphone addiction—which people often justify by pointing to the device’s usefulness in accessing information, handling banking and administrative matters, checking a child’s online school journal, or even supporting aspects of child development.

New patterns of behavior in digital civilization have produced a generation marked by bowed heads, weakened eyesight, “smartphone thumbs,” shortened attention spans, and poorly developed interpersonal skills, often accompanied by depressive and isolating tendencies. This last phenomenon—cyber loneliness—opens an abyss created by the illusion of online closeness.

Fake News as Misinformation

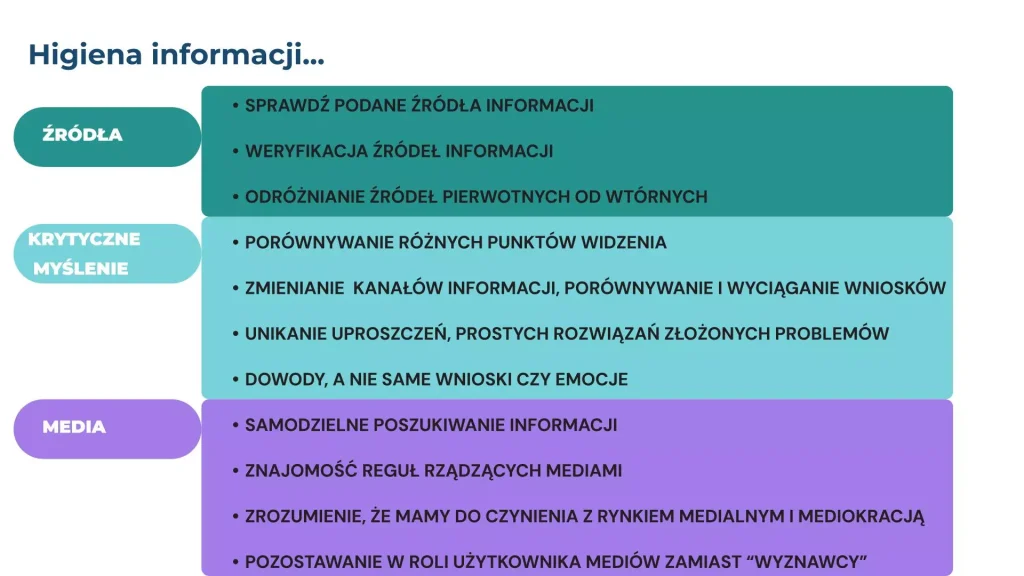

Information hygiene and the prevention of misinformation featured prominently in a presentation by Agnieszka Marianowicz-Szczygieł, psychologist, journalist, and President of the She and He Foundation. She framed her analysis using Harold Lasswell’s communication model, built around five core questions that define any message: who? what? where? to whom? and for what purpose?

She emphasized the limitations and challenges of modern communication, beginning with differences in the flow and durability of information that emerged as media evolved—from oral and written traditions, through print, to the internet and digital publishing, and now artificial intelligence. She also highlighted factors that shape how people communicate, process, and select information, including information overload, personal experience, feedback loops, social context, and the emotional state of the recipient.

As a result, personalized news and advertising deliberately target the recipient, who becomes the product rather than the subject matter itself. Emotionally charged headlines aim to capture attention, since greater popularity means more clicks and higher profits for content creators.

Marianowicz-Szczygieł stressed the need for independent verification of information circulating online, noting that “a fictional image of the world is often created based on emotions and personal beliefs rather than facts and evidence.” She encouraged mindful use of digital technologies and the internet, care for information hygiene, and caution in digital behavior—for example, limiting the amount of personal data shared online. As support, she recommended materials from NASK’s anti-disinformation campaign, available online (www.nask.pl/dezinfo), which offer practical tips and techniques for protecting against manipulation.

Legal Responsibility of Students: The Context of Cyberbullying

The Provincial Police Representative joined the debate by addressing the use of cyberspace for educational purposes in situations that violate safety rules. Representing the Central Bureau for Combating Cybercrime, established on January 12, 2022, he outlined the main characteristics of digital violence and the social roles involved in cyberbullying.

The spectrum of online harm includes both direct acts of aggression and sophisticated strategies of psychological manipulation carried out on digital platforms. These actions often remain anonymous, occur around the clock, persist over time, and prove difficult to identify. Speaker listed common forms of cyberbullying such as harassment, intimidation, ridicule, manipulation, and deliberate psychological pressure.

He warned of the scale of potential harm, citing statistics showing that 32% of Polish society spends time on online gaming platforms, with men accounting for 70% of users. Research from Jagiellonian University (2025) revealed that 9% of 700 surveyed teachers had experienced cyberbullying or cyberaggression from students or their parents. The most common forms included online defamation, attacks on social media forums, recording teachers without consent, creating memes, blackmail, account hacking, photo manipulation, fake teacher profiles, and disruptions during online classes.

Given the heightened risk, awareness of prevention and defense pathways is essential for educators, students, and caregivers alike. The police officer presented three main legal procedures used to protect victims of cyberbullying and prosecute perpetrators:

- Prosecution ex officio, covering crimes such as:

- incitement to suicide (Article 151 of the Penal Code),

- violation of sexual privacy (Article 191),

- stalking leading to a suicide attempt (Article 190a §3),

- fraud (Article 286).

- Prosecution upon request, applied in cases of:

- criminal threats (Article 190),

- stalking and identity impersonation (Article 190a),

- coercion through violence or unlawful threats (Article 191).

- Private prosecution, used in cases of:

- insult (Article 216),

- defamation (Article 212).

Two last proceedings begin at the initiative of the injured party.

Importantly, as the speaker emphasized, in both ex officio and request-based proceedings, victims do not need to collect evidence themselves. Law enforcement authorities carry the responsibility for gathering all evidentiary material, a fact worth stressing to those affected.

Conclusions

The reflections emerging from the Toruń Congress clearly show that the key to “breaking the digital leash” lies in returning to education grounded in authentic relationships and values, rather than relying solely on technology. Through shared experiences, participants left equipped with practical tools to combat disinformation and with legal knowledge essential for responding to cyberbullying. Ultimately, the event served as a reminder that conscious media use requires ongoing reflection on whether digital tools support human freedom—or instead lead to dependence and social isolation.