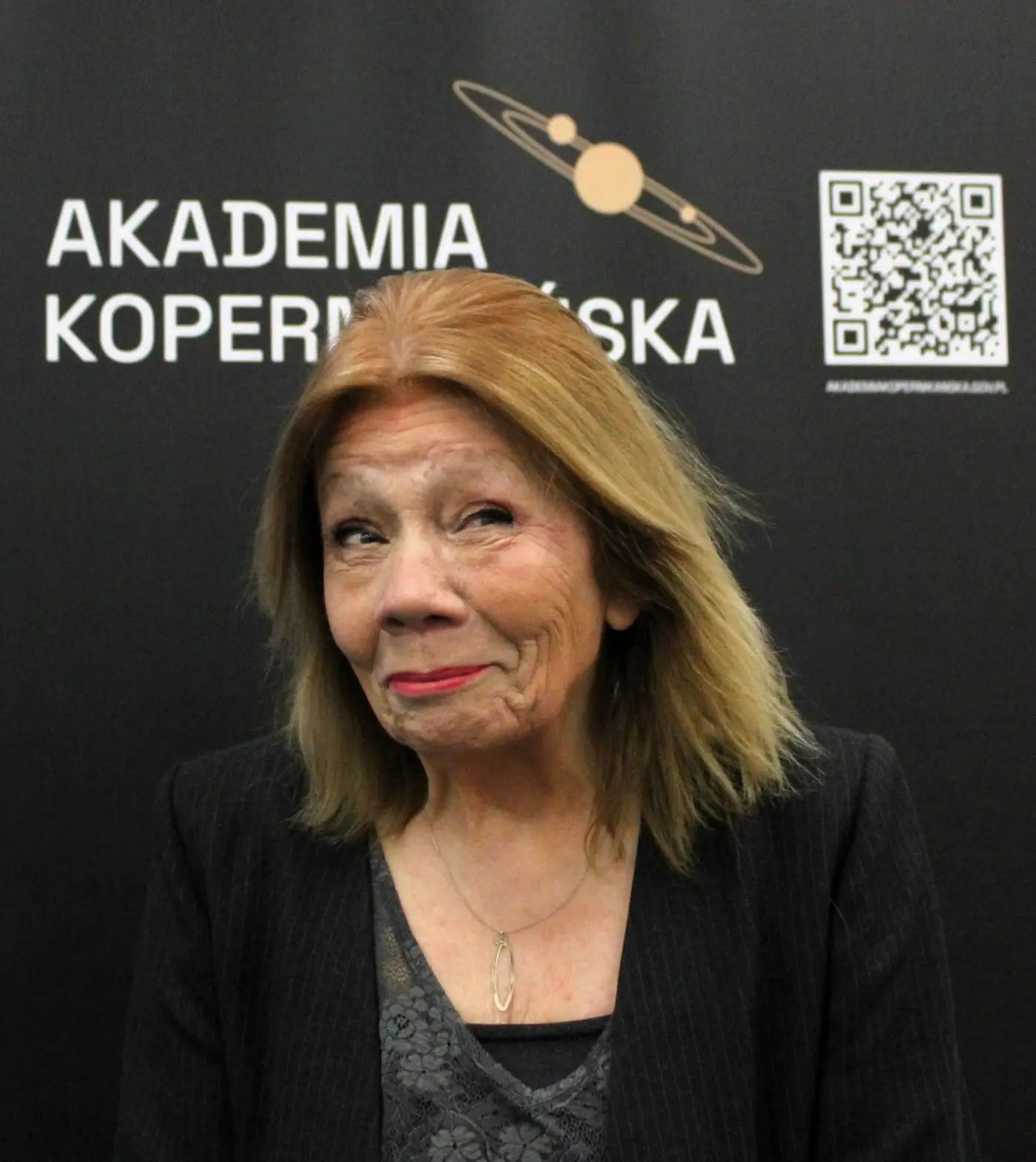

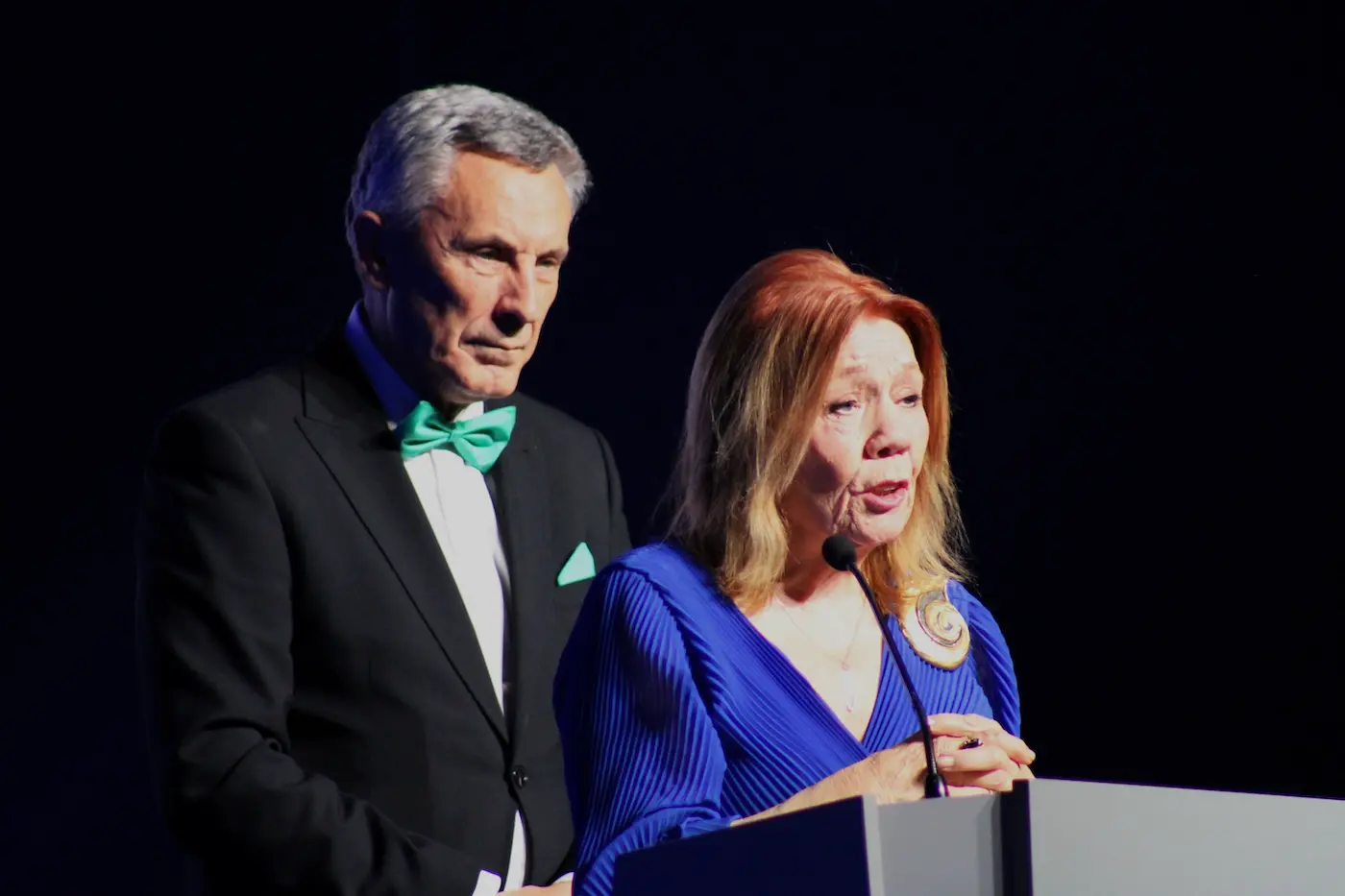

Interview with Professor Elżbieta Mączyńska

Professor Elżbieta Mączyńska, Honorary President of the Polish Economic Society, ranks among the most respected figures in Polish economics. She is also known as a remarkably warm and gracious person—direct, elegant and marked by exceptional personal culture. A graduate of the University of Warsaw and a professor of economic sciences, she has long been affiliated with the Warsaw School of Economics (SGH), where she heads postgraduate programs in real estate valuation. Her research focuses on finance, business valuation, and transformations of socio-economic models. She is also the creator of econometric models used to predict corporate bankruptcy.

Professor Mączyńska attended the 11th Congress of Polish Economists, held on December 4–5 in Poznań, where she agreed to a short interview. The conversation became an opportunity to reflect on the condition of contemporary economics, emerging paradigms of thought, and the challenges posed by a world immersed in uncertainty.

Q: Professor, you are taking part in a panel devoted to the theory and practice of New Pragmatism. In light of this year’s congress theme “Economics and the economy in times of uncertainty” does this school of thought offer innovative tools for understanding and managing today’s turbulence, in contrast to classical approaches?

I believe Professor Grzegorz Kołodko deserves great recognition for taking up this challenge and developing his original concept of New Pragmatism. The world is changing, yet since the beginning of Poland’s systemic transformation, the same model of capitalism has operated here—and to a large extent still does: neoliberal capitalism, which enjoyed uncritical dominance from the 1970s until the global financial crisis of 2008. That crisis showed clearly that this model no longer fits today’s reality and has in fact become harmful. It has led to numerous distortions, including massive global inequalities and serious harm to many countries.

This raises a fundamental question: what kind of model do we need in an era of rapid development in artificial intelligence?

In his concept of New Pragmatism, Professor Kołodko argues that such a model must be tailor-made rather than universal—unlike the Washington Consensus, which assumed one and the same solution for all, despite the profound differences among national economies.

One of this year’s congress guests, Professor Dani Rodrik of Harvard University, wrote the book One Economics, Many Recipes, which focuses precisely on country-specific models. Rodrik is a strong critic of neoliberalism, the Washington Consensus, and even some of his colleagues at Harvard who promoted it uncritically. In an interview with Rzeczpospolita on December 2, he recalled a remark from that book in which he described his fellow economists as “an arrogant bunch with little reason to be arrogant.” Asked in the same interview whether such views made him uneasy about attending the Congress of Polish Economists in Poznań, he replied that he was not afraid—he has criticized the profession for a long time, has thick skin, and feels well protected. At the same time, he expressed hope that Polish economists would prove far more reasonable than many of his colleagues and capable of non-stereotypical thinking.

Professor Kołodko clearly stands at the forefront when it comes to new ideas and the search for solutions and a new socio-economic model—one that could at least limit the distortions that so destructively shape today’s world.

The world is shaking and teetering, approaching catastrophic boundaries—some economists even say the very edge. It resembles a seesaw with two people sitting on it: one small, light, and slender; the other large, extremely heavy, and obese. It is obvious that the heavier one will catapult the lighter into the air. And that is exactly what is happening.

My colleagues from SGH, Professors Marek Garbicz and Wojciech Pacho, recently published a book titled The Concentration of Economic Power at the Beginning of the 21st Century. I consider it essential reading for anyone who wants to understand where the world is heading. The book shows the serious threats arising from the rapid concentration of economic power. As a result, states lose their role as decision-makers in matters fundamental to national development. Real power shifts to large multinational conglomerates—entities that some governments actually fear. We allowed this to happen. A prime example is the dominance of digital giants, with whom no country has yet learned to cope effectively. They do not pay digital taxes and resist doing so, despite benefiting enormously from national resources such as human capital, social capital, and infrastructure. This leads to a crucial question: is this the kind of world we want?

Many economists, including Professors Rodrik and Kołodko, argue that this path is a mistake and that we must seek alternative solutions. I fully share that view. Of course, this is not about ready-made recipes—it must be a process. Rome was not built in a day.

The world is currently experiencing a moment of transition—a civilizational turning point. The old, familiar industrial civilization is giving way to a new one shaped by digitalization and artificial intelligence. Under these conditions, a new socio-economic model will emerge gradually, but it must clearly aim to limit today’s distortions.

This will require action at institutional decision-making levels, starting from the very top.

Q: Professor, you are also a panelist in today’s session titled “Economics, Existential Questions, and the Global Climate Crisis.” In your view, does contemporary economics know how to effectively incorporate environmental costs into profit-and-loss calculations, or do we still treat ecology as an external constraint on growth?

Every discipline has its paradigm, and economics is no exception. Put simply, such a paradigm consists of at least three elements. The first concerns the subject of the discipline—the issues it studies. The second involves research methods and tools, which naturally differ across fields; a biologist, physicist, physician, and economist all work with different instruments. The third element, which is particularly important, concerns how scientific findings translate into practice.

As for the first element, neoclassical economics has severely neglected social issues, as if it had forgotten that economics is a social science. What is more troubling, some school textbooks even state that economics and ethics are completely separate domains. This ignores the fact that Adam Smith, the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher regarded as the intellectual father of economics and classical liberalism, first wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments and only later The Wealth of Nations, which in many ways extended those earlier reflections. Today, references to Smith focus overwhelmingly on The Wealth of Nations, while ethics and morality unfortunately fade into the background. Economics has thus undergone a form of reductionism—profit and business dominate everything else.

Many debates and publications create the impression that economics has been confused with chrematistics, the art of making money. But economics is not chrematistics. It is a social science rooted in philosophy—a science about people engaged in economic activity.

Economics includes many schools of thought, and each contributes something valuable. What matters is to examine them carefully and assess which ones best serve practice. And that is the key point: practical application.

Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz, in his 2010 book Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy, showed almost prophetically that the United States would lose its hegemony. This is a long-term process, but it is already clearly visible. Stiglitz even wrote that economics had become the most fervent cheerleader of neoliberal capitalism.

Under current conditions, economists must therefore pay particular attention to accounting for external costs and effects—externalities. Corporate profit remains a fundamental goal of business activity, though not the only one. When companies achieve profit at the expense of social well-being—when profits are privatized and losses socialized—we face a highly harmful phenomenon.

Climate change offers the clearest example. If we breathe polluted air, we fall ill, and the costs fall either on public health systems or on household budgets. This is why economists bear special responsibility for the third element of the paradigm: translating economic theory into practice.

Economics should serve people and exist for people—it should support material prosperity and improve quality of life, in other words, well-being.

Q: Since we represent the Copernican Academy, and our patron Nicolaus Copernicus also engaged with economics and the ethics of money, we would like to ask how relevant you believe this ethical dimension of economics remains today, especially in the context of inflation and its social consequences.

Today, this ethical dimension primarily concerns social justice—ensuring that unjustified inequalities do not grow, that the poorest do not become even poorer through no fault of their own, and that they are not exploited, including through the debasement of money, that is, inflation.Copernicus’ treatise on the debasement of coin remains relevant to this day, because inflation is nothing other than the debasement of money, and the poorest suffer the most from it. In that sense, Copernicus offered a prophetic warning about these socially harmful consequences.